Maintenance: battling the elements

Church buildings are resilient, but they are not indestructible. The basics – stone, slate, lead, timber, glass – require regular care and without timely intervention can quickly deteriorate. Routine maintenance for even a modest parish church can run to thousands of pounds a year. Major works, such as replacing a roof or repairing a tower, can easily cost hundreds of thousands of pounds.

These are not isolated cases but part of a wider trend where small issues can become bigger crises if not handled with the proper support. However, the National Churches Survey also shows the extraordinary resourcefulness of churches. Many are raising funds locally, maintaining buildings as best they can, and adapting them to continue to be relevant and welcoming.

What makes the difference is strategic, consistent, long-term support as well as targeted investment where it is needed most. This can not only save buildings from closure, but also enable them to adapt for modern use. Churches need to know what funds they can rely on in their planning, rather than putting together emergency bids. The question is not whether churches are willing to care for their buildings – they clearly are – but how to access financial support that can directly help. To achieve this, they need funding that’s easy to reach, enough to cover the real level of demand, and sustained over time.

Roofs: the first line of defence

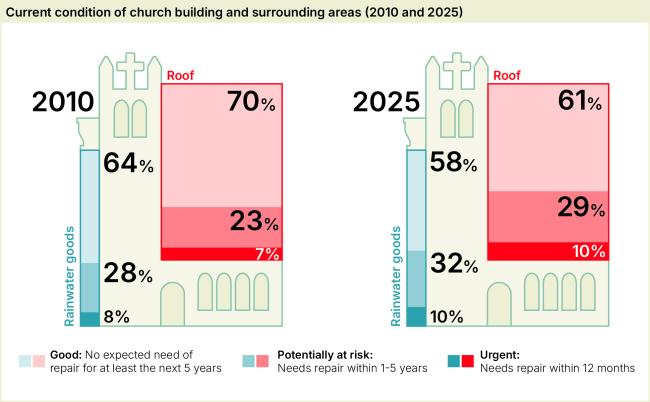

The 2025 National Churches Survey paints a stark picture: church roofs are under mounting strain. Roofs carry a particular weight in heritage terms, with these structures often requiring highly skilled repairs. Where these fail, damage spreads rapidly, as damp leads to more deterioration and weakened stonework, and puts the whole building at risk. The Survey shows that although 61% are reported to be in good condition, this is down significantly since 2010 (70%). Moreover, 39% now say their roof is at risk or in urgent need of repair, compared with just 30% in 2010. A leaking roof is not only a practical crisis but also a cultural and community one, putting at risk the craftsmanship that makes churches such distinctive national treasures and the spiritual home that so many rely on.

However, the Survey makes clear that churches are not standing by idly. Across the country, volunteers are fundraising tirelessly, often shouldering the overwhelming responsibility of repairing their roofs from within local means. In many cases, small-scale fixes keep buildings usable, but the scale of need far outstrips local capacity. Without intervention, small leaks quickly escalate into structural crises costing many times more to resolve.

This is why investment in roofs delivers extraordinary social return, as safeguarding the buildings in this way protects not just heritage but every community service that relies on these spaces.

Weathering the storms

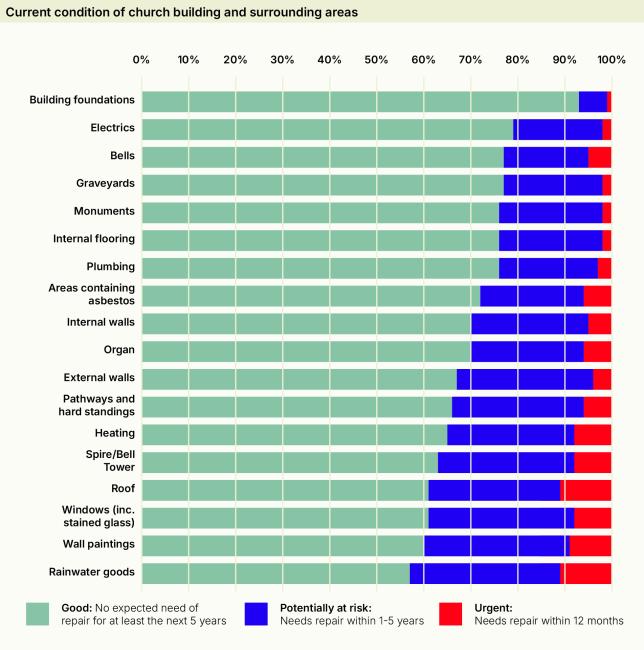

Beyond roofs, the Survey points to a gradual deterioration of church buildings across all categories. 32% of external walls now require repair (up from 23% in 2010) while 37% of windows need attention. Heating, plumbing and rainwater goods (gutters and drainpipes) are similarly vulnerable, as 41% report problems with rainwater disposal, and over a third (34%) with heating systems.

As climate change is threatening heavier rainfall and more frequent storms, churches face having to anticipate weather extremes that accelerate wear and tear on their buildings. This trend aligns with reports from Historic England which have flagged climate resilience as one of the most important issues affecting church buildings.4 By far the best thing a church can choose is to ensure its buildings are both windproof and watertight, from which many other steps can be taken.

The burden of resilience

Despite these challenges, many churches are far from passive. An encouraging 38% of churches report improvements in their building condition over the past five years, often achieved through targeted grants or the sheer determination of volunteers willing to take on daunting tasks. These successes demonstrate that when support is available, churches can not only stabilise but actively improve their buildings.

At the same time, 22% of churches say their building has worsened over the last five years, rising to 25% among listed churches where conservation work is more complex, more expensive, and often dependent on scarce specialist skills. Rural churches, with fewer volunteers and smaller congregations, are particularly vulnerable. What emerges is a picture of extraordinary resilience of both buildings and the people who care for them.

The roof was already failing – and then a storm hit

St Grada and Holy Cross is a Grade I listed remote rural church in the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall. It can

be seen for miles around and attracts thousands of visitors through its beauty and history.

But urgent roof and tower repairs are desperately needed and which are estimated to cost around £450,000. Water often floods into the building during periods of heavy rainfall and plants are growing in between the stones and gaps in the walls. Many community groups want to use the building – but only when it is safe and dry enough to do so.

The church has applied for many grants and has found innovative ways to fundraise, including hosting an annual sea shanty concert. But there is still a shortfall, made worse by changes to the Listed Places of Worship Grants Scheme.

Winter storms can be dangerous for old buildings and last winter proved to be the case for St Grada and Holy Cross. Tiles were blown off and the church was left with a hole in the roof. Areas of the church were forced to be closed off for safety reasons.

“We have got to save the church. It has stood here for hundreds and hundreds of years. It is not going to fall on our watch,” says Wendy Elliott, long-time supporter of the church.

Sudden changes make big financial headache for volunteers

Part of the Totnes landscape for more than 500 years, Grade I listed St Mary the Virgin is open from dawn until dusk every day and attracts 50,000 visitors a year, from people wanting to enjoy its heritage, watch a concert or just find somewhere quiet to reflect and pray.

It is on Historic England’s Heritage At Risk Register – listed as “poor” and facing “slow decay”. Through extensive local fundraising and grants from The National Lottery Heritage Fund, the National Churches Trust and many others, the church had secured £1.44 million to pay for urgent repairs and a facilities upgrade.

But a cap of £25,000 was imposed on the Listed Places of Worship Grant Scheme and the church was left with a shortfall of £130,000 VAT costs they would now have to find.

“This was a big knock for us. The project has been over 15 years in the planning and has already been through major restructuring,” explains Father Jim Barlow, Rector at St Mary. “Given that we have already been supported by nearly all the major

funders for church heritage projects, it has been a real struggle to find these extra funds. This is really disheartening for those who have

worked so hard and for the local community. The extra funds we have raised could have been used to do more works on the building to help take it off the At Risk Register, so for the sake of VAT a significant investment in the local heritage fabric has been reduced.”

Church repairs are often planned over many years, partly because of the need to fundraise locally to pay for the costs. Consistency is key, so that churches can plan for the future, and keep their buildings in good repair.

The hidden costs of repairs

Martin’s Memorial Church in Stornoway is on the Isle of Lewis – one of the islands that make up the Outer Hebrides off the north west coast of Scotland. This B listed church is unique in the Church of Scotland; it is the only church which has it specifically written into its constitution that no Gaelic services are permitted in the church. This was because the church came into existence as an English Preaching Station in 1875 when most of the services in Stornoway were conducted in Gaelic. Rev Donald John Martin, the first minister, had the vision of providing more English services to minister to the growing number of English–speaking people who came to Stornoway for the fishing industry. Martin’s Memorial is named after him.

In 2014, the church made big changes to move from being a ‘one day a week service only church’ to one that was open and available to support the community every single day. This meant financial investment by the church, as they employed two people to make this vision possible.

The church hasn’t stopped: they now employ 17 people and provide wide-reaching support in three areas: youth and schools, alcohol and drug support, and family support. This has meant making big changes to its dilapidated hall, which is directly connected to the church, to turn it into a dedicated family centre called ‘The Barn’. The £1 million project will provide the local community with additional support and activities for children and young people – support that is still sorely needed in the area.

Being located off the mainland can at times provide additional challenges for many places of worship: building materials often must be shipped in, and labourers, craftspeople and conservation architects may charge extra to cover their own travel and expenses. This can all increase any repair or refurbishment costs significantly.

“Our church was also so behind this work that they gave financially and sacrificially in recent years,” says Rev Tommy MacNeil. “This, along with significant support from the General Trustees of The Church of Scotland and other funders, means that ‘The Barn’ is opening its doors with the full cost of the project already being met.”

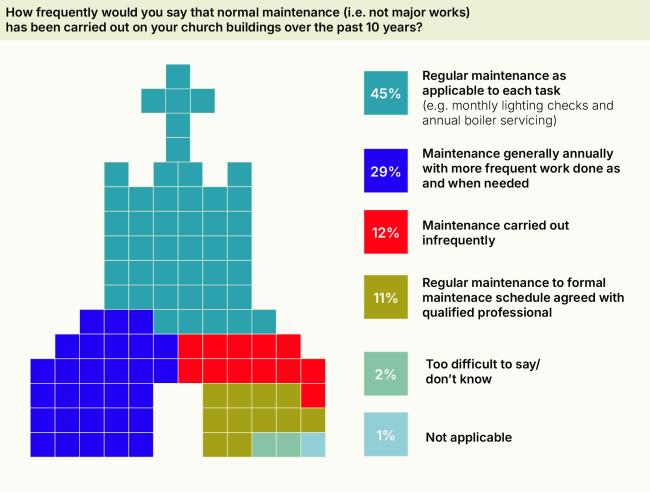

Inspections as acts of care

Regular condition inspections are one of the most effective safeguards to ensure a building remains in good repair. However, 71% of listed buildings have been inspected since 2021, compared to only 42% of unlisted ones. This reflects the regulatory framework around stewardship and also underlines the gap in routine checks for thousands of smaller churches. Where inspections lapse, problems are more likely to be discovered too late, leading to much higher repair costs. Worryingly, only 11% of churches in 2025 say they follow a formal maintenance schedule, down from around 13% in 2010.

For many others, building maintenance remains reactive or infrequent. If every church were supported to develop and maintain a regular inspection regime, countless small issues could be resolved early, preventing major damage and reducing financial strain. In the long run, investing in inspections is one of the most cost-effective ways of safeguarding both a historic building and the vibrant community life that depends upon it.

From facing demolition to becoming a vibrant music venue

Union Chapel in Islington was built between 1875 and 1877 by the nonconformist architect James Cubitt. Often described as a small cathedral, with original seating for more than 1,700, Union Chapel fell into neglect and was at high risk of demolition. Its survival is due entirely to the determination of local people who rallied to save and restore it.

Today, Union Chapel has been transformed into a vibrant hub of activity – not only an active place of worship but also an award-winning cultural venue hosting world class artists such as Amy Winehouse and Adele, and home to the chapel’s acclaimed homelessness charity, The Margins Project.

The chapel opens its doors as widely as possible, welcoming thousands each year, not only continuing as a place of worship but also for gigs, events, volunteering opportunities, and frontline services for people in crisis – all possible thanks to a continuous programme of conservation and maintenance of the Grade I listed buildings, assisted by grant funding organisations, generous donations and hiring out spaces. It’s managed by a secular charity, showing the combination of secular and faith can be achieved for buildings of heritage.

Most recently, the chapel was awarded £1 million from The National Lottery Heritage Fund for its Sunday School Stories project. This combines much needed repairs to the Grade II listed Sunday School and the Grade I listed Gothic Revival chapel with a major programme of cultural engagement: celebrating 30 years as a music venue and charity, telling over 200 years of Nonconformist history, and exploring the chapel’s proud record of social justice and activism.

Union Chapel stands today as living proof of how heritage buildings can be reimagined for the future – places that are beautiful, useful, and transformative.