Custodians of Cultural Treasures

There are over 20,000 listed places of worship in the UK, the vast majority of which are churches. Just over a fifth are Grade I listed, or equivalent, a third are Grade II* listed, and 40% are Grade II listed, according to data from the Historic Religious Buildings Alliance.

The 2025 National Churches Survey also asked churches about their artefacts, from fonts and memorials to local and national social heritage stories. What was revealed shows churches as living ‘memory banks’, places where generations have marked life’s key moments. Fonts are used to baptise children from local families; bells ring out for weddings; war memorials and plaques remember those lost in conflict. These treasures aren’t static relics, they are enlivened by worship, restored by volunteers, cherished by families, and discovered by visitors, connecting the spiritual and cultural threads of society.

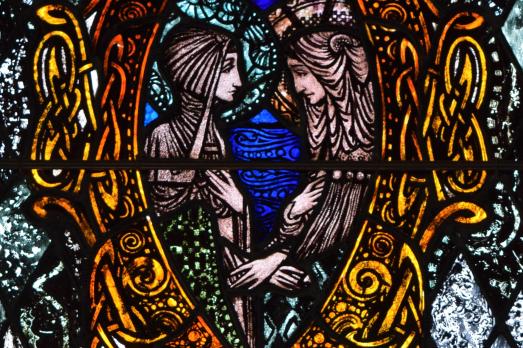

The Survey shows that stained glass stands out, appearing in 49% of churches as a work of artistic merit, and in 28% as a piece of national or local significance. These windows are visual wonders, telling biblical stories, commemorating local families, clergy, and benefactors, and reflecting creation. Fonts are the site of countless generations of baptisms and were highlighted by 27% of churches for their artistic quality, and by 22% for their local or national significance.

Passing art onto the next generation

St Macartan’s (Forth Chapel) just outside Augher in County Tyrone has turned itself into a tourist destination. People come from all over the world, as far away as New Zealand, to see the heritage inside this small rural church. And it all began from the church commissioning an architectural survey and making the necessary repairs – made possible by local fundraising and grant applications – to their mid-19th century building to protect the stained glass windows.

The church is home to four stunning Clarke Studio windows. Following their restoration, the church now works with local tourism bodies to promote tours around St Macartan’s. They also continue to work with nearby schools to share the local heritage and history. They even ran a stained glass art competition with a local school and held an exhibition of the artwork for the children and their families

to attend.

Canon McGahan, Parish Priest at St Macartan’s, shares why this is so important: “It was a tremendous opportunity in relation to the whole Harry Clarke stained glass windows, creating an awareness of the history attached to those windows, the history attached to the local church and the history attached to the local community.

“And when we reflected on the church, when we think that the people in the past gave us a tremendous legacy – they worked so hard to give us a building, a church which is so much part of the community.

“And bringing the present into the future – this was the vision, this was the hope, and this is what we continue to do.

“That is why we involved so many young people from our local primary schools in the art exhibition competition... we want these windows to be in good condition to pass them on, not only to the present generation but the generations to come."

One in five churches (20%) reported having memorials of artistic merit, while more than a third (35%) identified them as historically significant. These monuments often bear the names of local men and women lost in wars while others commemorate community figures, benefactors, or generations of families, telling quieter but equally important stories of local continuity, reminding us that churches safeguard not only the memory of conflict, but also the lived experience of everyday community life.

Other features highlight craft creativity – carvings (15% artistic; 13% of significance) and statues (13% artistic; 12% of significance), which range from medieval woodwork to Victorian sculpture. 12% of churches describe their “memory banks” of oral histories, photographs, and community records as artistically meaningful, and 22% see them as historically significant.

These cultural treasures are not static exhibits but continue to be part of peoples’ lived experiences – sung beneath, prayed before, passed by each week. Their loss would be a cultural catastrophe, but their preservation is a gift to future generations.

Securing Belfast’s maritime history

Sinclair Seamen’s Presbyterian Church is one of Northern Ireland’s most distinctive treasures, telling Belfast’s maritime story through every detail of its building. The pulpit is carved with a ship’s prow, bells and anchors hang from the walls, and worship begins each Sunday with a bell from HMS Hood. At the front stands a brass ship’s wheel salvaged in 1924, while an anchor painted on the floor marks the spot where couples have made their vows through the centuries.

This extraordinary heritage was at real risk. The sandstone building had deteriorated so badly it was placed on Northern Ireland’s Heritage at Risk Register. In 2024, a £50,000 National Churches Trust grant, together with a £10,000 Wolfson Fabric Repair Grant, enabled urgent stonework repairs to secure its future.

Sinclair Seamen’s continues to weave history into living community life. It opens weekly to visitors and

volunteers’, welcomes people from around the world who want to trace their family’s roots, and also runs children’s sessions, teaching knot–tying and local history. In a docklands area now undergoing regeneration, with a new university nearby, the church is once again drawing in students and young people. Its story shows how investment in heritage sustains not just buildings, but the cultural identity and local life they inspire.

Continue reading

The next section is 'What's at stake for the future of Welsh heritage?'.